The 18x Special Forces Candidate program has been around for over twenty years now. Many people interested in a career in special forces wonder if this is the best route and what their odds of success are.

In this article, I’ll give an overview of the program and why it was created, explain what to expect once you enter the program, and then give my view of the pro’s and con’s of the program from the point of view of a potential enlistee.

With all that in mind, I’ll give my recommendation for who should pursue the 18x program as their best route into Army Special Forces, and who would be better off considering an alternative route.

What is the 18x program?

18x Program Overview

In the simplest terms, the 18x program (pronounced “x-ray”, from the military phonetic alphabet) is an Army Enlistment Contract as a Special Forces Candidate.

There are a few things that are important to note right off the bat.

First, this is an Army Enlistment Contract, usually with a minimum 6-year commitment. The Army specifies this commitment, which is longer than many other enlistment contracts, because of the length of training required to become a Special Forces soldier (aka, “Green Beret”).

Second, note that this enlistment contract is as a Special Forces Candidate. There are no guarantees you will make it through all the training requirements and earn your long tab and beret.

In fact, statistically speaking, you probably won’t make it through, since Special Forces training has a much higher-than-average attrition rate. So what happens if you don’t pass one of the phases? I’ll cover that in more detail below, but it’s one of the most common questions I get from people asking if the 18x program is their best option.

Third, the 18x program is an enlisted-only contract. Special Forces Officer Candidates have different requirements, including time-in-service, before they are eligible to attend Special Forces Assessment and Selection (SFAS), so there is no direct-to-sf route for them.

If you’re not up to speed on the differences between officer and enlistment contracts, I suggest you read up on it to help inform your decision. For now, I’ll offer a quick note on the difference within Army Special Forces.

Officer vs. Enlisted in Army Special Forces

Enlisted Non-commissioned Officers (NCO’s) make up over 90% of the Army Special Forces ranks. Additionally, Special Forces Warrant Officers (180A), which are composed entirely of former SF NCO’s, are another 5%. That means commissioned officers account for only 5% of the Army Special Forces Ranks.

SF NCO’s primary role is on a Special Forces Operational Detachment-A (SFOD-A), aka a team. SF NCO’s will spend the majority of their career on an ODA, with occasional rotations into other assignments, such as an instructor at the Special Forces Qualification Course (Q-Course).

SF Officers, by contrast, will only spend 18-26 months on an ODA, with most officers landing around 24 months. After that, they spend their time between staff positions, additional education, and if they qualify, in higher command positions (Company, Battalion, Group).

The reason for this is because Army Officers have very strict timelines for the type of assignments and professional education they must complete. It wasn’t always this way: the Army Officer Special Forces Branch was created in 1987. Prior to that, officers would leave their primary career branch to do a stint in Special Forces, and eventually return to their main branch – or not, and hang out in Special Forces, usually sacrificing promotion and long-term career prospects.

With that context, keep in mind that if you want to be a true Special Forces operator, the enlisted route will help you achieve that goal. You’ll sacrifice some of the pay and education opportunities available to officers, but you’ll get far more team time and real-mission experience.

18x Program History

The 18x program was created after 9/11 when Army Special Forces quickly found themselves at the forefront of the war in Afghanistan. Army Special Forces focus on training and leading indigenous forces made them the perfect fit for the fight against the Taliban. The first teams on the ground in Afghanistan earned the nickname “Horse Soldiers”, since they were seen riding horses into battle alongside the Northern Alliance.

A statue at the foot of the One World Trade Center, built to replace the World Trade Center Towers brought down by the 9/11 terrorist attack, commemorates these soldiers.

Because of their language and cultural knowledge, Army Special Forces quickly became the unit of choice for military and political leaders in the new “Global War on Terror” (GWOT). With increasing deployments, there was a need to backfill over-deployed teams, and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumself called for adding an additional battalion of SF soldiers to every active duty Special Forces Group.

The 18x program was created as a way to increase the pipeline of potential SF candidates and help expand the ranks to meet the growing need.

Those Damn X-Rays

Prior to the 18x program, soldiers needed to have a minimum of 2 years in the Army, and be of the rank E-5 (Sergeant) before they were even eligible to attend SFAS. The average SF candidate prior to the 18x program had between 5-8 years of time in service prior to attending SFAS.

Because of this, there was initially strong push-back from many existing SF soldiers. How could a civilian kid off the street come straight to an ODA, even if he passes all the required training?

In the early 2000’s, in the early years of the 18x program, there were cultural clashes on the teams between older operators and the brand new 18x’s. Special Forces team culture was always more laid back and less formal than the “Regular Army”, but this was partly due to the fact that everyone had done their time in the regular army – “SF appreciation time” – and knew the fundamentals well.

18x’s, by contrast, had spent their entire Army career – after Basic Training and Airborne School – within the Special Forces community. They lacked an understanding of basic Army formalities, and were often perceived as arrogant, undisciplined, and immature, which earned them the nickname “SF Babies”.

There was a pushback within the SF community, and for a time, senior SF Operators started implementing a more “regular army” cultural norms – uniforms during all duty hours, stricter haircuts, no “uniform mods” except on deployment. All this was done to try to install some basic Army culture into the new recruits.

Prior to the 18x program, anyone who made it through the full SF training pipeline and joined the teams usually stayed for a full 20-year Army career. They already had 5+ years in when they went to selection, and at least 7 years in when they made it to a team. So, staying the full 20 was the norm.

The 18x program changed that as well. Since 18x soldiers could end up on a team as early as 2 years into their Army career, they could potentially serve 4 years on a team and then leave the Army for a civilian career. And many did. Some returned to a civilian career they had left for a few years to serve their country, while others went on to use their GI Bill to pursue a degree.

Regardless, this was another source of tension.

Generational Shift

The last generation of old school SF soldiers who served prior to the 18x program have all retired or moved into positions outside of the teams. That means that every soldier on the teams today has served alongside 18x’s for the entirety of their SF career. That doesn’t mean there aren’t still some team guys with an old-school attitude towards the x-rays; there certainly still are. But, it does mean that x-rays are seen as less of an anomaly compared to before.

It also means that many senior SF leaders, including many current team sergeants and a few Sergeants Major, were themselves x-rays. They went through the crucible of having to earn the respect of their more seasoned peers, and then managed to work their way into leadership positions. This can be a double edged sword for new 18x’s joining the SF ranks.

On the one hand, these leaders know that 18x’s can become highly skilled operators, just like any other soldier. On the other hand, they know the skepticism 18x’s still face from their teammates coming out of the infantry and other combat arms units prior to SF, and the reputational damage to the 18x program that one bad apple can have.

Today, a squared-away, high-performing 18x will quickly be accepted and respected on a team. But for a low performer, there are still plenty of SF soldiers who will be quick to dismiss them as spoiled SF Babies too immature for the job.

18x Program Structure and Training Timeline

18x Minimum Requirements

The Army specifies minimum requirements for every type of enlistment contract. For the 18x Special Forces Candidate contract, those minimum requirements are as follows:

- Must be a U.S. citizen or permanent resident with a valid Green Card

- 19 to 34 Years Old

- High School Diploma or GED

- No medical issues

- No Law Violations (necessary to qualify for a Secret Security Clearance)

- ASVAB Score: 100

- ASVAB General Technical (GT) Score: 110

Keep in mind that these are minimum requirements for the enlistment contract. There will be another set of minimum requirements to be able to attend SFAS, and candidates who only meet the minimum requirements have a very high attrition rate.

The training timeline for the SF program is as follows:

- Basic Training and One Station Unit Training (Infantry): 22 weeks

- Airborne School: 3 weeks

- Special Operations Prep Course: 4 weeks

- Special Forces Assessment and Selection: 3 weeks

- Special Forces Qualification Course: 6 months – 2 years (dependant on MOS and Language)

Total training time: 1–2+ years

This timeline doesn’t account for breaks between training. For example, after graduating OSUT at Ft. Moore (formerly Ft. Benning), you may have to wait 1-2 weeks until the next Airborne class starts. If you’re training overlaps Christmas or other Holidays, you’ll likely have a 1-2 week break then.

In total, it takes most 18x’s who go through the training pipeline without any recycles 1.5 to 2.5 years to earn their Green Beret.

Now let’s take a more in-depth look at each of these phases of training (note: SFAS and the SFQC are topics that merit a more in-depth discussion, but for the purposes of this article, they’ll be given an overview).

Basic Training and Infantry Training (OSUT)

- 22 weeks

Every Army enlistee goes through two types of training: Basic Combat Training (BCT), also known as “boot camp”, which teaches the most basic fundamentals of being a soldier, and Advanced Individual Training (AIT), which teaches the skills needed for your chosen Military Occupational Speciality (MOS). For many soldiers, they will attend Basic Training at one location, then head to another location for AIT.

In the case of certain combat arms MOS’s, such as Infantry (11B), Basic Training and AIT are combined into “One Station Unit Training”. The distinction between Basic Training and AIT are blurred, since you’ll spend the entire time with the same platoon, the same drill sergeants, in the same barracks. You may get some occasional privileges in later phases of training, like a few hours “off” to visit the base PX on a Sunday, but you’ll be a basic trainee the entire time, and you’ll be treated as such.

The Army increased it’s Infantry OSUT training from 14 to 22 weeks in 2018, where it stands today.

During OSUT, your entire day will be controlled by the Drill Sergeants, including what and when you eat and sleep. As far as physical conditioning, OSUT is like a funnel: if you show up in below-average shape, you’ll leave in better shape than when you got there. If you show up in great shape – as someone who takes the SF program seriously must – you’ll leave in worse shape than when you showed up. Your diet, training, and sleep will all suffer at Basic Training. You’ll have to get back into shape before you’re ready for SFAS.

Airborne School

- 3 weeks

After OSUT infantry training, you’ll head across Ft. Moore to Airborne School to conduct Airborne Training. Airborne School (aka, Jump School) is essentially 2 weeks of practicing parachute landing falls (PLF) – aka, practicing falling down – followed by jump week, where you’ll complete 5 static-line parachute jumps.

Airborne School will be “easy” compared to OSUT, and you need to use this time to start getting back into shape: sleep, eat better, and ease back into workouts outside of duty hours. You’ll have access to the base gym, the PX to buy supplements, and your weekends will be free. You won’t be sacrificing much: the social scene in Columbus, GA is nothing to write home about.

Special Operations Preparation Course I (SOPC I)

- 4-6 weeks

After Airborne School, you’ll be relocated to Ft. Liberty (formerly Ft. Bragg), where you’ll be for the remainder of your training.

The Special Operations Preparation Course (SOPC – pronounced “Sop See”) is a pre-selection training program designed to get SF candidates into shape for Selection. If you show up to SOPC without a strong fitness foundation, 4 weeks won’t be enough to get you ready for selection.

SOPC I will take place at Camp Mackall, in Southern Pines, North Carolina. If you succeed on your journey to become a Green Beret, you’ll spend a lot of time at Camp Mackall.

SOPC I will focus on running, ruck marching, land navigation, bodyweight training (push-ups, pull-ups, lunges, squats, etc), and practicing the obstacle course “Nasty Nick”.

The goal of SOPC I is simple: get you ready to pass selection.

Special Forces Assessment and Selection (SFAS)

- 24 days

Special Forces Assessment and Selection (SFAS) will be the hardest phase to-date for SF candidates, and it will be the phase that starts to weed out most people in the training pipeline. Selection rates for all soldiers tend to hover around 30%, though it fluctuates from class to class.

At SFAS, candidates can be dropped for two reasons: medical (med drop) and integrity violations. Other than that, the only way to not complete the course is to quit – aka, voluntarily withdraw (VW). The top reasons for not completing SFAS are:

- VW

- Med Drop

- Integrity Violation

That said, the primary reasons behind VW’s and Med Drops are not being physically and mentally prepared. Candidates who are insufficiently prepared physically will end up struggling mentally as well. As they get beat down over the grueling 24 day selection process, they end up getting injured or quitting.

Completing the full 24 days is no guarantee of being selected. In fact, only about 50% of candidates who complete the full 24 days of training get selected. The rest are “24-day non-selects” – those who completed the full 24 days, but didn’t get selected.

Some things you can expect at Selection:

- Psychological training

- Lots of rucking and running

- Obstacle course

- Land Navigation

- Team Week – carrying awkward, heaving objects in a group for miles, on top of your rucksack

If you pass SFAS and are selected, you’ll be given the chance to specify your preferences for SF MOS and Language, which will impact the Special Forces Group you are assigned if you complete the Special Forces Qualification Course (SFQC). There are 5 active duty SF Groups, each with a regional focus.

Special Operations Preparation Course II (SOPC II)

- 3 weeks

SOPC II is designed to teach basic patrolling and small unit tactics to non-combat MOS soldiers who have been selected to attend the Special Forces Qualification Course (SFQC).

Because 18x’s have never served in an actual infantry unit, they are included in this training.

Don’t be deceived by the benign–sounding name of this phase, or the fact that you passed selection and have been selected. Depending on the instructors, this can be one of the most difficult, grueling phases of the entire training pipeline.

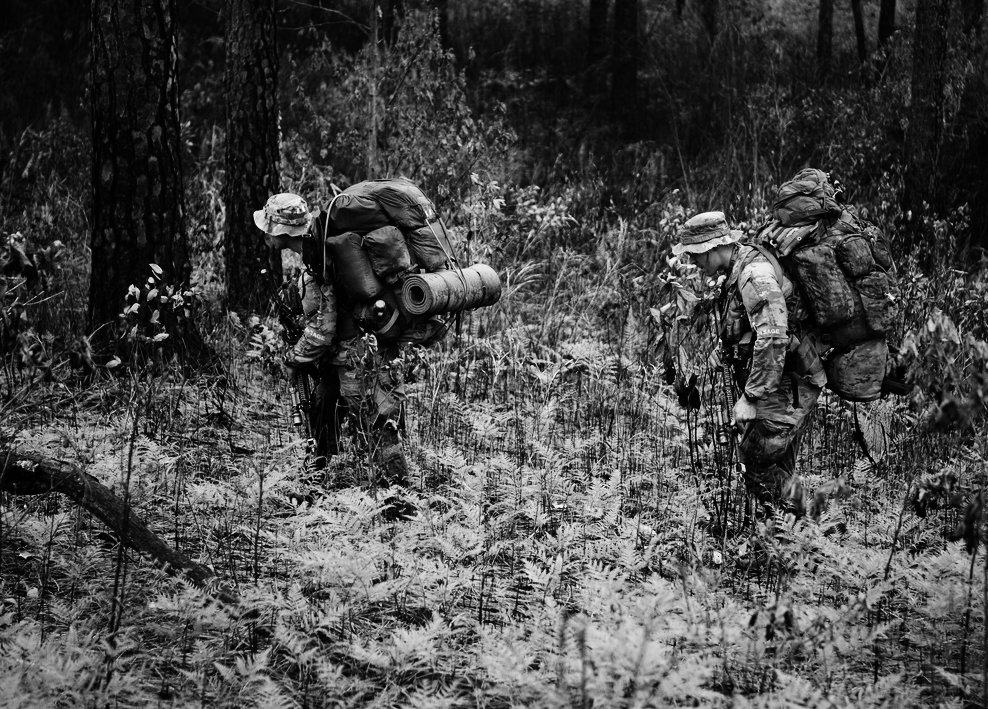

You’ll spend 3 weeks in the woods at Camp Mackall carrying around 100lb rucks, learning to write Operation Orders (OPORD), Warning Orders (WARNO), and plan and lead patrols.

You’ll get very little sleep, very little food, and because you’ll be outside nearly the entire time, you’ll be at the mercy of the weather as well. Heat, cold, rain, snow. But if you’re going to be a Green Beret, that’s something you have to get used to.

Special Forces Qualification Course (SFQC)

- 6 – 24 months

The Special Forces Qualification Course, usually called the “Q-course” for short, will be where you learn all the skills needed to serve as an SF Soldier on an ODA. The structre of the Q-course moves around from time to time, but the basic phases of the Q-course are as follows:

SFQ-Course Phases:

- Phase I. Special Forces Orientation Course (6 weeks): This phase covers history, doctrine, organization, command and control, core tasks and mission, Special Forces attributes, Special Forces mission planning. It also covers some foundational individual skills that will be needed for future phases, like land navigation, introduction to small-unit tactics, an overview of each SF MOS, PT and nutrition, etc.

- Phase II. Small Unit Tactics (SUT) (13 weeks): This phase teaches the fundamental tactics of combat units, including the principles of patrolling, planning, and leadership. Expect to do lots of ambushes and raids.

- SERE C: (3 weeks) This is the final phase of SUT, though at times it’s been considered its own phase. Here you’ll learn Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape, culminating in a week-long realistic training experience.

- Phase III. MOS Training (14 weeks): Here, you’ll go through one of 4 courses:

- 18B: Weapons Sergeant

- 18C: Engineering Sergeant

- 18D: Medical Sergeant

- 18E: Communications Sergeant

There is also an 18A course for Detachment Commanders, but that is for officers. 18x’s aren’t eligible for it.

- Phase IV: Robin Sage (Unconventional Warfare Culmination Exercise) (4 weeks): Here you’ll be grouped into an ODA with other students that is structured like a real team, with representatives from each of the MOS’s. You’ll conduct some training, in-depth mission planning, and then be dropped into the pine woods of North Carolina for a simulated guerilla warfare exercise. Expect extra-heavy rucksacks, an onerous g-chief, and uncooperative guerillas.

- Phase V. Language and Cultural Course (18-24 Weeks) The difficulty of the language determines the length of the course during this phase. Easier languages, like Spanish, will be 18 weeks, while more difficult languages like Arabic and Chinese, will be 24 weeks. To pass this phase, you must earn a 1/1 in speaking/listening on the Oral Proficiency Interview (OPI).

If you make it through all that, you’ll earn your Green Beret, Special Forces Long Tab, and head out to join your first team.

What are the Pros and Cons of the 18x Special Forces Candidate Contract?

Pros of the 18x Contract

First, the pro’s of the 18x contract. I’ll offer my perspective compared to the alternative of enlisting in another MOS and then going to Selection a few years into your Army career.

The 18x contract is the most direct path into Army Special Forces.If you succeed, it is the fastest way to end up on an Army SFOD-A and start gaining first-hand experience as a Green Beret. If you spent a 20-year career in the Army, you could realistically do 10-15 years on a team and be an incredibly skilled and experienced operator. If you spend 3-5 years in the Regular Army prior to going to selection, that’s time you won’t get as an SF soldier.

You’ll avoid the politics and obstacles you might face to going to Selection if you enlist on a regular infantry contract. The truth is that not everyone in the Army loves SF, and you might end up with a commander, first sergeant, or platoon sergeant who hates SF and does everything to keep you from going to selection. In extreme cases, I’ve heard of guys getting assigned terrible, time-consuming details in the weeks leading up to Selection to make it harder for them to train.

The odds of something that extreme are small, but it is possible.

With the 18x contract, you can skip all of that Regular Army nonsense and politics. You’ll get 4-6 weeks of dedicated SFAS preparation during SOPC I, something you’ll never get in the Regular Army. Even if your Regular Army command is supportive, you’ll have to train on your free time, which means nights and weekends.

Then there’s the bonus. 18x contracts probably offer better bonuses than other enlistment contacts, but this can vary.

Cons of the 18x Contract

The biggest downside – if you want to call it that – is what happens if you don’t pass. In reality, that’s a downside for anyone who goes to Selection, or who passes Selection and makes it to the Q-course.

The real question is whether the odds of you failing are higher or lower than the average soldier. Unfortunately, the statistics on that aren’t publicly available, so I would assume a similar pass rate as someone coming from the regular army, which is around 25% of those that qualify for and are accepted to SFAS.

If you don’t make it all the way through the Q-course – if you wash out at some point for any reason – you’ll be assigned to a unit based on the “needs of the Army.” Most likely, you’ll end up in an infantry unit in the 82nd Airborne on Ft. Liberty, since you’ll already be Airborne Qualified.

In my opinion, there are three unique challenges that 18x’s face compared to regular army soldiers attending selection.

First, they have a rushed training pipeline. OSUT, Jump School, SOPC I, then Selection. It will be tough to get into or even maintain peak physical condition in OSUT and Airborne School, so you’ll really only have 4-6 weeks at SOPC to get ready for selection.

Second, 18x’s lack the experience and skill of a soldier who’s been in the Army for a few years. There’s some tacit knowledge that comes from going to the field, going on ruck marches, going to the range, and deploying that is tough to teach explicitly. You learn how to pack your ruck, what to put at the top and bottom, how to water-proof your stuff, what kind of cold weather gear you need and when to put it on, how to take care of your boots and feed, the most important parts of an MRE, etc.

Finally, most soldiers that have been in the Regular Army for a few years have moved into a leadership position, even if it’s just a fire team leader in charge of 4 soldiers. That knowledge and experience will be incredibly helpful, especially during SUT and Robin Sage when you have to plan and lead patrols.

Who Should Pursue the 18x Contract

None of the challenges mentioned above are insurmountable, but they do start to give clues about what it takes to succeed as an 18x: maturity, intelligence, physical fitness, grit, determination, and a team attitude.

I think someone ages 23 – 26 is in the ideal age range for an 18x contract. This gives you the minimum maturity needed to succeed in the Special Forces pipeline. The SF pipeline isn’t like Ranger or SEAL training, which is completed in 6 months. It’s a grind that takes over a year and requires a high degree of academic aptitude as well.

But, you’ll also be treated like crap for much of the time until you graduate: from the Drill Sergeants at OSUT and from Cadre and Instructors at the Q-course. That’s why I recommend 26 as the ideal upper-limit. Spending one to two years in student mode isn’t easy, and for someone who’s been around a little longer, or has an established civilian career, it will be even harder. That doesn’t mean it can’t be done – I served alongside guys who left high-paying private equity jobs for an 18x contract.

Based on the above attributes, here’s what I recommend as the ideal person to pursue the 18x contract:

- 23 – 26 years old

- Some college or college graduate

- At least 1 year of work experience

- Played competitive high school sports

- High test scores (ACT, SAT, ASVAB)

- Experience with a foreign language

- Have traveled abroad

- No legal issues (so you can get a Secret Security Clearance)

You don’t need all those attributes, but the closer you are to the above, the better your chance of succeeding and performing well on a team.

Most importantly, ask yourself how bad you want it and what you’re willing to give up to become a Green Beret. If you’re doing it for external validation or to impress some girls, you should be a Navy SEAL.