“The things you own end up owning you” – Tyler Durden

Ways of Defining Training Minimalism

Training minimalism could mean many things. It could mean spending the least amount of time in a week or month training. It could mean doing the fewest number of exercises possible while seeking the largest impact. It could mean using the fewest workout variations — repeating the same one or two workouts. It could mean using the least amount of equipment possible to accomplish your training goals.

There is inevitably overlap between all these definitions of training minimalism. If you do fewer exercises, your training could take less time. If you have less equipment, you may do fewer exercises, which may again, take less time.

But not necessarily. You could attend a HIIT class where you perform 10 different exercises for one minute each with a one minute break. That would take 20 minutes — minimal time — but use 10 pieces of equipment and a variety of movements. Similarly, you could own nothing but a barbell and some plates — minimal equipment — and spend 2 hours going through endless variations of the Olympic lifts.

Over the last few years, I’ve explored several varieties of training minimalism. Today, I want to focus on training minimalism from an equipment and space perspective. This is useful for anyone living in an apartment in the city, like I was at the time I conducted this experiment, or anyone else who has limited space or prefers not to accumulate too much stuff. As Tyler Durden said in Fight Club, “The things you own end up owning you.”

For the 10+ years I spent in the Army, I rarely had to consider training “minimalism”. Not only was working out expected and part of the job, training time was built into the schedule, and I had access to world-class training facilities. No matter what workout program I followed, I had access to the equipment I needed. From standard barbells, dumbbells, and treadmills to tires, sledgehammers, climbing ropes, gymnastics rings, sleds, boxes, and C2 rowers, I had my choice.

After leaving the Army two years ago, things changed. I moved into a 1-bedroom apartment in the city with limited space. There weren’t any good gym options close by; they all required a long commute, were too crowded, or were too expensive. While I have always wanted my own home gym, the version I imagined required quite a bit of space: I imagined a garage with a squat rack, custom Olympic lifting platform, pull-up bar, and a few accessories like a C2 rower, some kettlebells, and a medicine ball. Maybe an assault bike to round it out.

The reality of city life was different. With limited space, I still wanted to put together a home gym that allowed me to hit my training goals: lose body fat, gain muscle, and feel good (rather bland and generic, I know).

It’s true that from a pure minimalist perspective, a pure bodyweight routine would require the least equipment. But I wanted my home gym to allow me to perform some key movement patterns with multiple options for exercises and weight in each category: squat, lunge, hinge, push, pull, carry. I also wanted to be able to perform some basic accessory work for muscle stabilization. It’s tough to meet that criteria with no equipment. My goal was to put together something small, compact, and relatively inexpensive.

The Training Minimalism Home Gym

To that end, I came up with the following “home gym” solution that could fit in the corner of my apartment:

- 1 x TRX

- 1 x 50 lb kettlebell (KB)

- 2 x 25 lb dumbbells (DB)

- 1 x exercise mat

- 1 x set resistance bands

That’s it. Five pieces of equipment which took up no more than two square feet of valuable floor space in my 1-bedroom city apartment.

Using the minimalist home gym

The movements

Here’s how the equipment applied to the six major movement patterns and accessory work described above:

- Squat

-KB goblet squats

-DB squats

-DB thrusters - Lunge

–Dumbbell lunges

-TRX single-leg lunges (weighted and unweighted) - Hinge

–KB swing

-Kb single-arm, single-leg deadlift

-DB Romanian deadlift

-TRX hamstring curl - Push

–Push-ups

-Deficit push-ups (with dumbbells)

-TRX Push-ups

-DB overhead press

-KB single-arm push-press - Pull

–TRX Rows

-KB single-arm bent-over row

-DB double-arm bent over row - Carry

–DB carry

-KB suitcase carry - Accessory work

Core

-Hollow-rocks

-Planks

-Curl-ups

-Bird Dog

Shoulder stability

–Banded extensions

-Shoulder shrug push-ups

-Shoulder shrug TRX rows

Hip stability

–Banded walk forward/backward

-Banded side step

-Glute bridges

There was additional room for variety by including exercises like KB snatches, burpees, etc, but I chose to leave those out and focus only on the exercises listed above for each movement category.

THE WORKOUTS

I wanted the way I approached my workout composition to be simple as well, while also providing room for variety and progression. I accomplished this by grouping my workouts into three categories: A, B, and C.

- Workout Group A:

-Squat

-Hinge

-Pull - Workout Group B:

–Lunge

-Push

-Carry - Workout Group C:

–Circuit with all 6 movements

I varied the movements in each group for every workout so I didn’t perform the exact same movement for two workouts in a row. I increased the difficulty of exercises by performing more reps per set, shortening the rest-time between sets, or using tempo sets (example: 5-second descent, 1-second pause, 5-second ascent). I also performed core and accessory work at the beginning of each workout.

The results

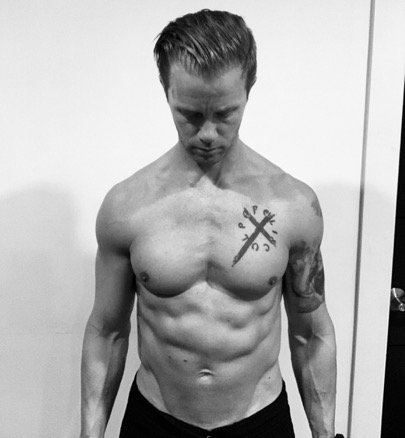

After eight weeks of training this way, I found that I had met my blandly stated goals: I did indeed gain muscle, lose body fat, and feel great. Retrospectively, I found it useful to look at my training experiment from other considerations as well.

Strength: Overall, my pure strength went down while my muscular endurance went up. I went from being able to perform 51 consecutive unbroken pushups to 63. Similarly, I went from performing 33 goblet squats (50 lb kb) in one minute to 41. But, when I visited a gym, I found that my bench press and squat had gone down. There’s no substitute for the central nervous system (CNS) loading provided by heavy lifts like the squat and deadlift.

Mobility: My mobility increased, possibly because I was working with lighter weights which allowed me to hit a full range of motion more consistently. My joints felt better and minor aches and pains which I had felt before were gone or significantly reduced.

Time: Because I didn’t have to commute to the gym, wait for equipment, or walk across the gym to get from one exercise to the next, my workouts became much more efficient. Where my typical trip to the gym might cost a total of 2 hours between the commute, the workout, and any social interaction, my home workouts were typically only 40–50 minutes from start to finish. I was doing five to six workouts a week, so I saved five to six hours each week.

Variety: There were times when I missed going to the gym, seeing the people there, and doing movements like heavy deadlifts or back squats. While I varied my routine to ensure that I never got bored, there were times when I wanted a change of scenery from my apartment. Of course, that can happen when you go to the same gym every day as well.

training seasons

Overall, my experiment in equipment and space training minimalism was a success. I met my fitness goals, saved time and money, and learned some new movements and workouts. I eventually did get a gym membership, but there are still days when I can’t make it to the gym. I still have all the tools in my apartment to stay on track and fewer excuses for skipping a workout.

Training minimalism isn’t a tool for someone who wants to get into absolute peek shape. That requires more time, equipment, and dedication. But training minimalism can be a great tool for certain seasons of life, or seasons of training.

training minimalism for the lifelong trainer

Anyone who has been training for years knows that training can become a grind and wear you down physically and psychologically. Incorporating periodic seasons of training minimalism can be a great way to let your body and mind recover. When you view your training goals over the span of years, rather than just weeks or months, incorporating a one-to-two month training minimalism phase two-to-three times a year is a great way to keep yourself from stagnating. Or worse, from burning out, developing an overuse injury, and quitting.

training minimalism for the professional

Everyone experiences ebs and flows throughout the course of their career. There may be busy periods marked by long hours, and their may be slow periods marked by short weeks and long weekends. There may be periods where you are working to deliver a critical project, launching a business, settling into a new role after a promotion.

Training minimalism may not be right for every phase of your career, but it might be just what you need to get through an especially busy phase where your career demands more of your time than usual. Having a minimalist routine in place, and the equipment to execute it, can help alleviate the stress of a long day.

training minimalism for the athlete

If you compete in sports, or are in a profession that requires a high degree of physical fitness, training minimalism can be an effective tool to keep yourself in shape without wearing your body down.

Tactical athletes are one group that can benefit from scheduled periods of training minimalism to reduce overuse injuries while still staying in shape for the job.

variations of training minimalism

This article focused primarily on training minimalism with regards to equipment and space, and how the equipment and routine you use can affect other aspects of your training. But, equipment and space aren’t the whole story of training minimalism. Training minimalism can also mean reducing the time it takes to work out, reducing the volume of training, and reducing the number of movements you use. It might mean focusing on your minimum effective dose of training.

The best way to figure out how it fits into your training routine is to start experimenting. Hopefully this article gives you a basis to do that.